Rolande Souliere, artist. Shelf display for an olfactory journey through the four directions. Photo — Charles Cousins, AGA.

Scents of Movement, Scents of Place

Lindsey Sharman

Artworks, like perfumes, reveal themselves over time; the longer you stay with them, the more nuanced ideas are uncovered. Described by their top notes, middle notes and base notes, perfumes unfold and require time to fully appreciate.

Presented at the Art Gallery of Alberta (AGA) from September to December of 2022, Scents of Movement, Scents of Place used olfactory art projects associated with movement and place to uncover broad ideas of colonialism, preconceptions, and racism. Through the use of scent, it allowed visitors to have unconventional aesthetic experiences that challenged the ways they know and interact with the world around them.

Top notes are what confront you immediately and then fade. In Scents, the top note was the concept of place. How does scent relate to places we know, places we can get to, those we cannot, or perhaps we don’t want to? Also, memory played a part, as scent is the sense that is most strongly and directly connected to our long-term memory. Artist collaborators Sans façon and the artist Brian Goeltzenleuchter faithfully recreated scents of places and times drawn from individual personal memories, generously sharing the intimacy of a past moment through its particular scent.

Sans façon, artist duo. Installation in Scents of Movement exhibition. Photo — Charles Cousins.

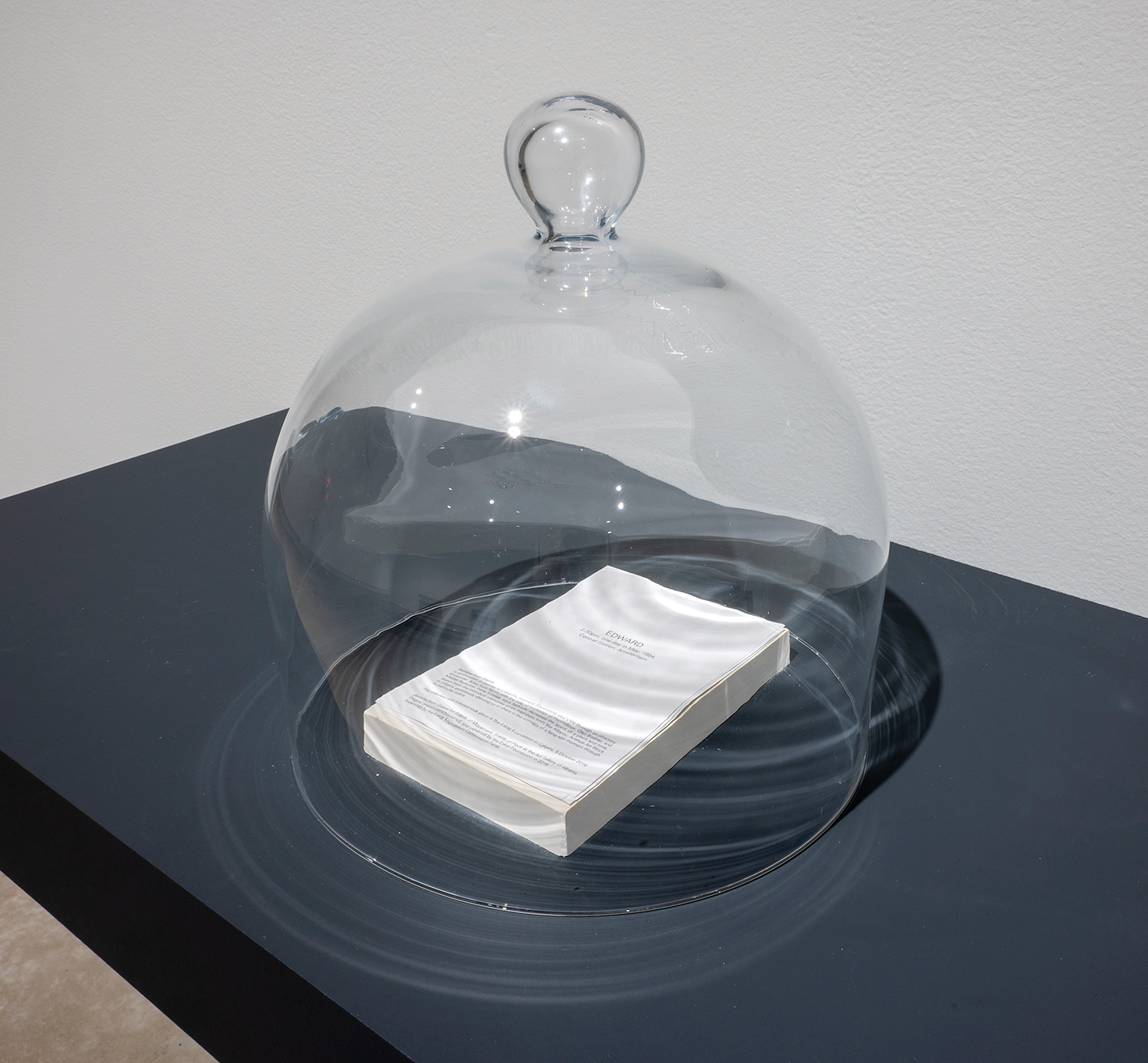

Sans facon’s Jasmine from Grasse, journeyed to specific nostalgic moments in someone’s life, and faithfully recreated the scent of a moment from the past for six individuals, with each scent infused into take away stories that are displayed under glass bell jars.

In Scents of Exile, Brian Goeltzenleuchter worked with refugees to recreate the smells of their now unreachable homes. Each station consisted of a freestanding hand sanitizer dispenser filled with a custom solution where the antiseptic and ubiquitous scent of hand sanitizer had been replaced with highly personalized scent memories. Those using the hand sanitizer are enveloped by someone else’s experience, whose memory is absorbed into the skin, injecting multiple individual experiences into institutional infrastructure.

The middle notes are the core of the scent, and within the exhibition are all movement-based. Travel, migration, immigration, navigation and transportation. The exhibition moved viewers from one stage of life to the next, through themes of time travel, globalization, trade and the delineation of space.

Millie Chen and Evelyn von Michalofski’s satirical work, The Seven Scents, used scent to navigate the tourist experience encouraging visitors to think critically about care, travel and leisure. Inspired by the legendary exoticism and adventure of The Seven Seas, The Seven Scents invited visitors to relax in seven cruise ship deck chair recliners, listen to seven soundscapes, and inhale seven scents to create the ambiance of locales both near and far.

Playing with and critiquing the prevalence of exoticism in commercial perfumery, Chen and Michalofski blend scents like coconut and lime with local Edmonton smells. For example, the Antarctic deck chair is paired with the audio of a ferry dock and the scent of gasoline. Distilling together sound and scent with romance and reality and blending the fantasies of escape with the odious actualities of tourism.

A view of two installations in the Scents of Movement exhibition. In the background, Abbas Akhavan, artist, Untitled Garden. In the front, Millie Chen & Evelyn von Michalofski, artists, a row of deck chairs part of The Seven Scents. Photo — Charles Cousins.

Abbas Akhavan’s work Untitled Garden, 2008/2022, an 80-ft-long planter filled with fragrant cedar trees, explored how trees are used worldwide in civic and corporate plazas, often disguising security barricades and how hedges were one of the first ways to delineate public and private property. The trees and their scent are native to North America but the scale and shape of the installation invokes how cedars were transported in early trade between North American colonies and Britain to become a key tool used to enclose common land in the seventeenth century, making public lands unreachable.

The base notes of a perfume are what is gradually revealed over time. Scents of Movement, reflected this by exploring broader notions of life, death, a myriad of worldviews (or worldsenses), subjectivity, colonialism and what we can know through our nose.

Indigenous artist, Rolande Souliere presented the Four Directions with sacred medicines—cedar, tobacco, sweetgrass and sage. Embedded within an abstract rendering of the Anishinaabe medicine wheel, the work reflected a worldview that is inclusive of physical and spiritual worlds, kinship, birth, death, the afterlife and the eternal through four limited edition fragrances. For example, the scent for North represented Winter, incorporating the concepts of purity and renewal, Elders, the mind and sweetgrass.

Sita Kuratomi Bhaumik traced the real and imagined spatial histories of “curry,” using it as a fragrant stand-in for colonization and notions of both identity and the Other. To Curry Favor is a work made by adhering curry powder to the walls in a decorative abstract pattern. Bhaumik explores how stereotypes manifest throughout all our senses. Kari is a Tamil word with multiple meanings, including “a tree whose leaves are used in South Indian cooking.” This word passed through Portuguese and then British colonizers, emerging as “curry” to describe any saucy spicy dish. Bhaumik says, “As a word created by the colonizer to describe foods of the colonized, curry is an inadequate word for many delicious dishes.” For this installation across from Sir Winston Churchill Square in Edmonton, the artist dedicated the piece to her great grandmother, Sarada, who died along with 3 million people in the Bengal famine that began in 1943. The famine was caused by British policies in India, under Churchill’s leadership.

Scents of Movement, Scents of Place was intended to challenge the supremacy of vision within museum spaces, upheld through classist and racist ideologies like those found in the work of influential early nineteenth century natural historian Lorenz Oken, who invented a sensory hierarchy of human races—with the European “eye-man” at the top. This false hierarchy led Europeans to believe that the “lesser senses” were unsuitable when appreciating art and artifacts and sight was deemed as the only appropriate sense to understand aesthetics. Hsuan Hsu’s work The Smell of Risk: Environmental Disparities and Olfactory Aesthetics also demonstrates the violence that air maintenance, control, and conditioning enacts on the poor and the marginalized, including devastation settler colonialism has reaped on Indigenous smellscapes.

Sita Kuratomi Bhaumik, artist. To Curry Favor, 2022. The installation and a close-up view of the curry powder and adhesive design. Photo — Charles Cousins, AGA.

The exhibition forefronted more-than-visual ways to learn and interact with the world and prioritized non-visual aesthetic experiences, putting forth that culture is not held and learnt in a sterilized environment but that smell—among other intangible things—holds culture, place and can create belonging and be called upon through all of our senses.

To protect visitors, the exhibition focused on opt-in interactions for fabricated scent experiences, while natural things that inherently had a scent (trees, curry, sweetgrass) were left open. Experiences where visitors were empowered to decide how they engaged and at what speed they encountered the scents in the exhibition were favoured.

Finally, like perfume, the exhibition didn’t lose site that it could offer enjoyment. While the themes within this exhibition are serious and important it was also an exhibition that was just fun. Reserved adults melted into playfulness as they delighted at familiar and unfamiliar scents while exploring with their noses. Children took what they learnt in this exhibition to openly express how the rest of the museum smelled to them, they saw the exhibition as permission to interact with the world through their noses far beyond the exhibition space. M

Lindsey Sharman is based on Treaty 6 territory in Edmonton and has been the Curator of the Art Gallery of Alberta since 2018. She is interested in sensorial art experiences and the aesthetics of olfaction.